Whoever is elected as the next President of France, he or she will wield more power than almost any other leader in Europe. What’s more, with an unprecedented eleven candidates, of whom five were credible contenders, the choice presented to French voters has been more complex than ever before. In Tréguennec, a Brittany village with just over 300 inhabitants and where we have our second home, the main sentiments expressed by our friends about the election were feelings of conflict and uncertainty.

Presidential elections in France are staged affairs, with voting held on two Sundays a fortnight apart. We were in Tréguennec for the month leading up to the first stage and for the week following, and witnessed the vote that decided which two candidates would stand in the definitive second stage.

As with all democratic systems, responsibility for the outcome ultimately rests with individual voters living in defined communities, and in several ways the Tréguennecois are unusual. First, the village is traditionally left wing. Until eight years ago the Mayor was a Communist, and in last year’s regional elections, the numbers who voted for Marine Le Pen’s ultra-right National Front Party – around 6% – was, as a proportion, amongst the lowest in France. Second, inhabitants, or should I say those neighbours with whom we are close, are very happy to discuss their views openly. Third, details of the voting pattern of its 273 registered electors are open to public scrutiny since the village is a single, identifiable, constituency.

Amongst our neighbours, none bemoaned François Holland’s decision to stand down and all felt it would be a tragedy if Marine Le Pen were to become President; if a tactical vote were needed to avoid this outcome, most – but not all – were prepared to compromise. Finally, amongst our friends there was a strong feeling, as was expressed throughout France, that the population at large had been betrayed by the two main parties. Both had become self serving rather than representing constituents’ interests.

A strong consensus also emerged about the candidates themselves. Setting aside the unanimous rejection of Le Pen, a vote for François Fillon, the Right’s representative, was viewed as unthinkable, while voting for Benoît Hamon, representing the now fractured traditional left, was seen as a waste. In all, the favourite was Jean-Luc Mélanchon, the far-left candidate who was seen to speak sense, to echo old-time, socialist values, and to have the skills to counter Le Pen’s rhetoric. Finally, Emmanuel Macron’s proposals were considered as no more than vacuous bluff. However, since he was the one candidate, according to opinion polls, with enough support to take on the far-right, a strategic vote for Macron – a ‘vote utile’, as the French put it – would be a legitimate option.

Soon after polling opened on the day of the first round, I was in our village hall – our only polling station – to see how voting worked in France and, later, to watch the count. I was greeted warmly by three neighbours. Claude, in his official position as Mayor, was standing beside the ballot box; Rémi, a councillor, was sitting at a table with one pile of empty envelopes and eleven piles of named voting papers, one for each candidate, – just one to be placed in the envelope when voting. The third neighbour was Béatrice, another councillor, who was sitting beside the electoral list.

When I arrived there were already nine votes in the ballot box, and Pierre, who came in soon after, would provide a tenth. His identity card was checked, his presence on the electoral list verified, and he picked up one envelope and eleven voting cards. After a few moments in the privacy of a curtained booth, and having jettisoned ten named voting papers, he posted his envelope containing the paper of his choice in the ballot box, at which point the Mayor proclaimed ‘Has voted’. Pierre then signed against his name on the register and Béatrice stamped the date on his voting card. Everything was over in less than five minutes with no fuss, no queue, and no armed guards. Oh the delights of village life!

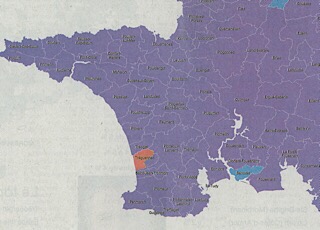

After voting closed, the ballot box was emptied and with the help of nine others the Mayor started the count. Some forty or so villagers, from children to eighty-year olds, had gathered at the back of the hall to see fair play – it was almost a family affair. Thirty minutes later the Mayor announced the results; Mélanchon had won convincingly. In response to the news the onlookers could be seen quietly smiling. The next day, figures for the whole region were published in the local paper as a colour-coded map, and there, in a sea of Macron purple was the solitary red Mélanchon island of Tréguennec, an outcome achieved on a turnout several points higher than in France as a whole

Whatever happens in the next round, the people of Tréguennec have had their say, and, in the circumstances, I think they were right. Indeed, had others in France done the same, the next round would have been a fascinating prospect. Now it will be a tactical battle between Macron and Le Pen in which the electorate will be choosing between an unknown centrist dream and an extremist right wing nightmare.

Joe – Thank you for your ‘insider’s’ view of French politics. This Sunday’s final vote will be tense, as two-thirds of far-left supporters of Mélanchon have stated they will NOT vote for centrist Macron in order to thwart Marine Le Pen – they will abstain or cast blank votes.

I wonder whether that strategy may appeal to residents of ‘red’ Tréguennec – some of your neighbours may not be so open about their decision this time!

LikeLike

Dear Veep, Amongst our friends, and they were more than happy to speak, around a third of those who voted for Mélanchon (most) or Hamon said they could not/would not vote for Macron, and two thirds said they would for sure, or almost certainly, vote for him. On the basis of the Treguennec position, Macron can expect to get the bulk of the left wing votes. So, ultimately, next Sunday’s vote will probably not be close. Yours, Joe

LikeLike

Fascinating. But how is he going to select his candidates for the elections in less than a month?

LikeLike

Dear Ian,

Macron’s search for candidates started in January, and he believes that ‘en Mrarch! has, or will have, enough candidates to contest all 577 seats. From the outset certain criteria were established so there will be a large proportion from civic society and around half will be women. Whether they are elected is another matter. My hunch is that he will not get enough to have a working majority in the National Assembly. Yours, Joe

LikeLike